Since we began our mission to end distracted driving after the death of our daughter Casey, we’ve continually found that the way to be most impactful is to appeal to the groups of drivers who need the most change. What we learned early on is that while teen drivers are most at risk of being killed in distracted driving-related crashes, their age group is actually the most willing to be champions for safe driving.

EndDD’s founder, Joel Feldman, has pointed out that while presenting to high schools all over the country, he found out that many students’ parents drive distracted with them in the car. “I ask the students to raise their hands if their parents drive distracted, and 70 to 80 percent of them raise their hands.” Then, during evening presentations, Joel has a chance to address the same students’ parents. He asks them to raise their hands if they would do anything to keep their kids safe. “Predictably, all of their hands are raised,” he told The Day in 2019. “Then I would say, ‘Keep your hands up, but only keep them up if you haven’t driven distracted with your kids in the car.’ Virtually all the hands go down.”

Getting parents to rethink the way they drive quickly became an important part of EndDD’s mission. It’s the reason why our organization began presenting to middle schoolers several years ago. While the students are not of driving age, hearing about the impact of distracted driving can not only teach them safer habits before they get behind the wheel, but it can also give them the conversation tools to speak up when their parents or others drive distracted with them as passengers. It’s also why we developed elementary school lessons; while more of the students still have a decade or more before they can drive, we know that they are effective advocates for change, even now, after they have been taught to speak up and let mom and dad know that their distracted driving scares them.

We’re attacking this core focus to keep as many kids safe as possible, so other families do not have to endure the pain that we have after losing our daughter. But we still have a long road ahead, as the current statistics of distracted parents are pretty bleak. In a recent survey, the National Safety Council (NSC) identified the event types that are most effective at stopping distracted driving (such as a car crash, a near-miss incident, driving laws, or new technology), how parental driving behavior changes when children are in the car, and the effectiveness of children speaking up against distractions. Of the 1,250 respondents nationwide, the NSC found that four in five parents admit to using their phone while driving, whether in-hand or hands-free – even though most parents consider calls and text messages to be distracting. Below is a more in-depth summary of the NSC’s report on distracted parents.

Driving Behavior

Based on the NSC’s survey, more than half of drivers consider themselves to have “above average” driving behavior, and the rest consider themselves “average,” yet half of drivers also admit to making or answering phone calls. About one-third of the survey’s respondents say they will glance at or read notifications or texts, or send texts, and nearly one in four will use social media while driving at least occasionally. Most of the drivers surveyed say they have observed other drivers put themselves or others at risk, or could have contributed to a crash, because they were distracted by technology.

Distracted Driving During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has had an impact on the way people drive. Nearly four in ten drivers have been taking shorter driving trips the last couple of months, and one-third have stopped driving daily. However, for nearly four in ten respondents, their driving habits have not changed during the pandemic. One in four believe behaviors such as speeding, technology distractions, and driver fatigue are occurring more often during this time.

Combating Distracted Driving and the Power of Children

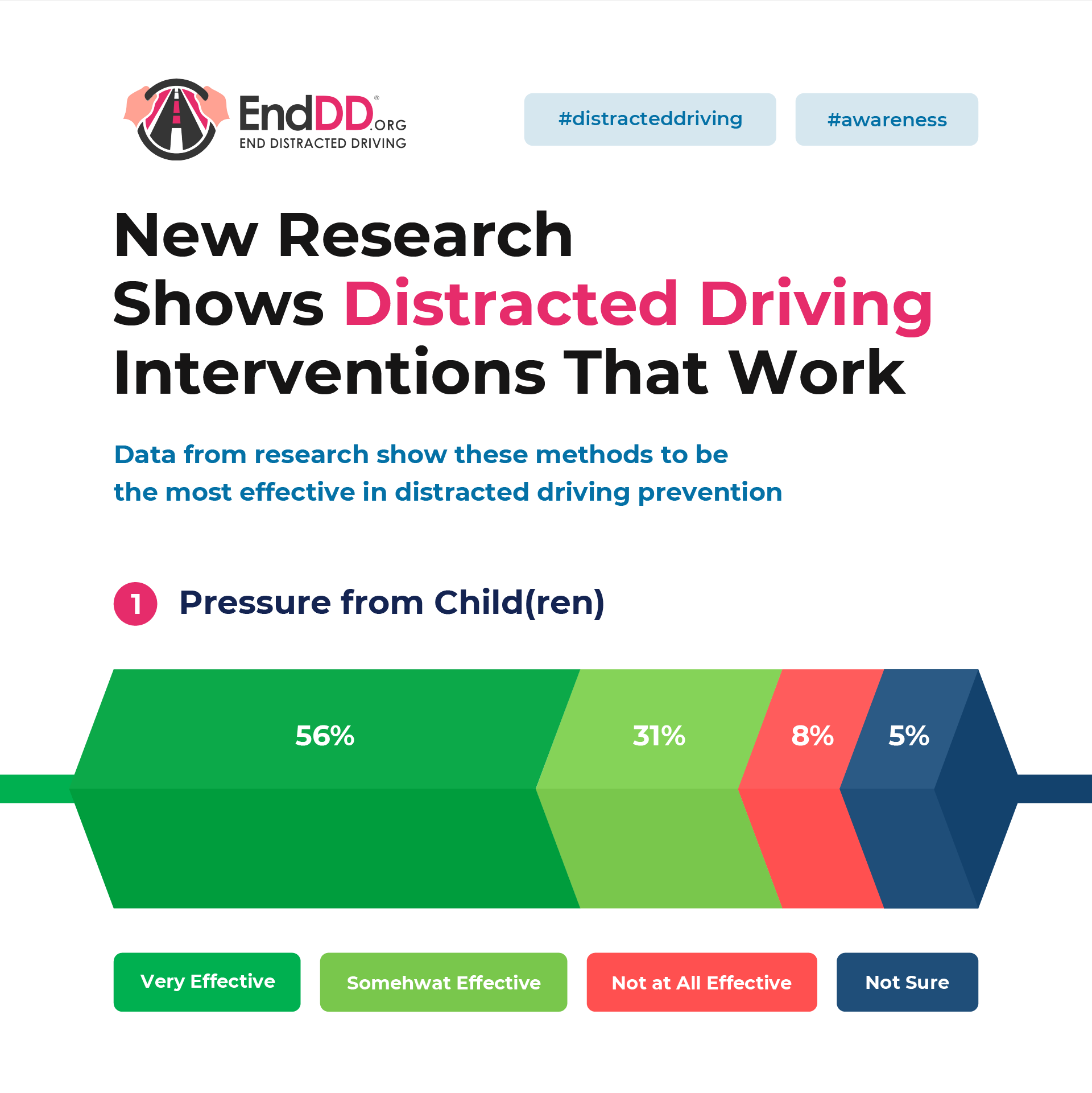

The NSC set out to learn whether kids have a role in their parents’ driving behavior. Survey respondents agree that pressure from children is most effective at deterring them from using their phone while driving. Almost four in ten parents have had their children comment on their driving, and more than half of those parents had a child age 12 or younger speak up about the behavior.

The NSC’s report underscores the importance of the work we are doing to help kids speak up when their parents are distracted. Our elementary school program, Kids Speaking up for Road Safety, teaches the S.A.M. tactic, which is an effective way for children to communicate that they do not feel safe when their driver is distracted. When a driver tries to use their phone or is otherwise distracted, we teach kids to remember the acronym S.A.M.:

See a problem.

Address the problem using a respectful and non-confrontational “I” statement, such as: “I don’t feel safe when you look at your phone while driving.”

Make an action plan together.

“The long and short of it is, kids are willing to hold that distracted-driving person accountable: ‘You are disrespectful. You are selfish,’” Joel told the Philadelphia Inquirer in 2019 when he announced a distracted driving awareness curriculum for elementary schools. “But adults, he said, generally say it’s dangerous and then keep doing it. “We have to change the culture so … it’s no longer socially acceptable, and I think that’s how we do it — listening to the kids. We hold people accountable.”